Translate this page into:

Coronary artery perforation treated with Viabahn stent graft: A case report

*Corresponding author: Adam Schmitz, Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, United States. awschmit@iupui.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Schmitz A, Diab N, Butty S. Coronary artery perforation treated with Viabahn stent graft: A case report. Am J Interv Radiol 2020;4:15.

Abstract

Coronary artery perforation is a rare but serious complication of percutaneous coronary intervention. This case report describes a patient with Grade III perforation of the left anterior descending coronary artery who underwent placement of a peripheral arterial stent graft due to persistent contrast extravasation refractory to conventional coronary stent graft placement and balloon tamponade.

Keywords

Coronary artery disease

Coronary artery perforation

Endoleak

Percutaneous coronary intervention

INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery perforation (CAP) is an infrequent but severe complication of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) which can result in cardiac tamponade, myocardial infarction, and death.[1] Current mainstays in treatment include close observation, placement of coronary-specific stent grafts, and balloon tamponade. When these measures fail, emergency surgical intervention may be required.[2] This case report describes the management of a Grade III left anterior descending (LAD) CAP with a peripheral arterial Viabahn (Gore Medical, Flagstaff, AZ, USA) stent graft. One previous case report has detailed a similar procedure utilizing a slightly smaller Viabahn stent graft in a patient experiencing a Grade III perforation of the right coronary artery.[3]

CASE REPORT

A 79-year-old male with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type II diabetes mellitus was admitted to the hospital for 3 weeks of progressive dyspnea on exertion and bilateral lower extremity edema. Diagnostic left heart catheterization revealed an ejection fraction of 36%, moderate mitral regurgitation, and severe coronary artery disease involving the right coronary, circumflex, and LAD arteries. Prior to this encounter, the patient had no documented history of heart disease. Due to these findings and his medical comorbidities, he was not deemed to be a surgical candidate and he elected to undergo PCI. Before the procedure, medical therapy was initiated with aspirin 81 mg, atorvastatin 80 mg, and a ticagrelor loading dose of 180 mg.

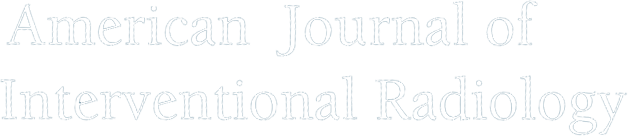

Pre-procedural systemic anticoagulation was achieved using intravenous heparin. In the cardiac catheterization laboratory, right femoral artery access was obtained and an Impella (Abiomed, Danvers, Massachusetts, USA) device was placed without complication. Initial coronary angiography revealed 80% stenosis in the proximal LAD [Figure 1].

- A 79-year-old male with 3 weeks of progressive dyspnea on exertion who was subsequently diagnosed with coronary artery disease involving the circumflex, right coronary, and left anterior descending arteries. Initial angiography showing 80% stenosis (arrow) in the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery.

Orbital atherectomy was performed using a Diamondback 360 Coronary Orbital Atherectomy System (Cardiovascular Systems Inc., St. Paul, MN, USA) and a 3.5 mm x 16 mm Synergy drug-eluting stent (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) was deployed in the proximal LAD. Following stent placement, there was rapid extravasation of contrast from the LAD, and the patient was found to have a Grade III CAP.

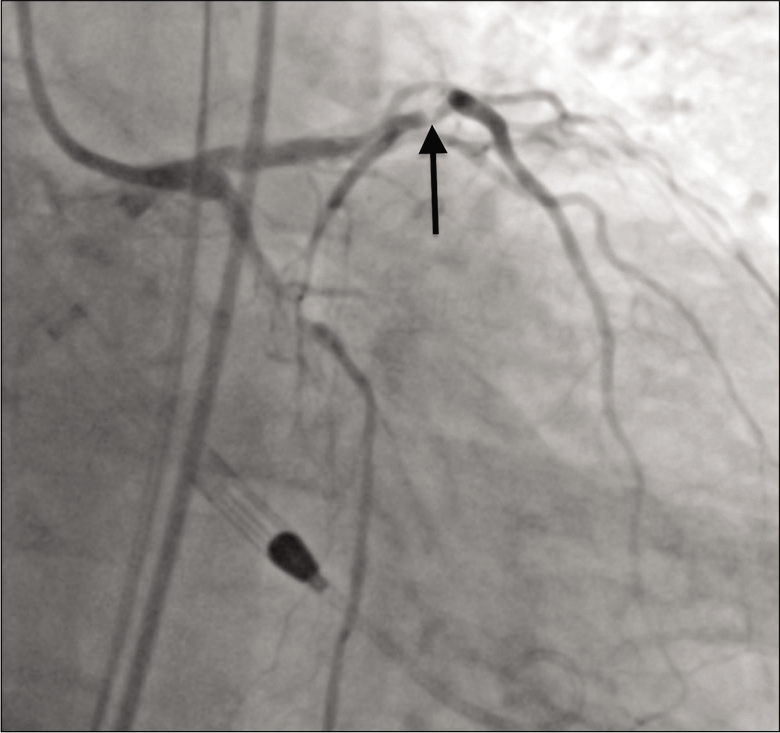

The patient rapidly became hypotensive and an echocardiogram showed a large volume hemopericardium. A pericardial drain was placed, and the massive transfusion protocol was initiated. Anticoagulation was reversed with protamine, and a 3.0 mm × 20 mm PK Papyrus stent graft (Biotronik, Berlin, Germany) was placed in the LAD and serially dilated to 5.0 mm in an attempt to seal the defect. Balloon tamponade was then performed at the site of perforation, but complete thrombosis of the LAD occurred. The patient was once again anticoagulated and aspiration thrombectomy was performed. This restored antegrade flow in the LAD, but angiography revealed persistent contrast extravasation [Figure 2].

- A 79-year-old male with 3 weeks of progressive dyspnea on exertion who was subsequently diagnosed with coronary artery disease involving the circumflex, right coronary, and left anterior descending arteries. Angiography showing active contrast extravasation (arrow) from the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery immediately following stent placement.

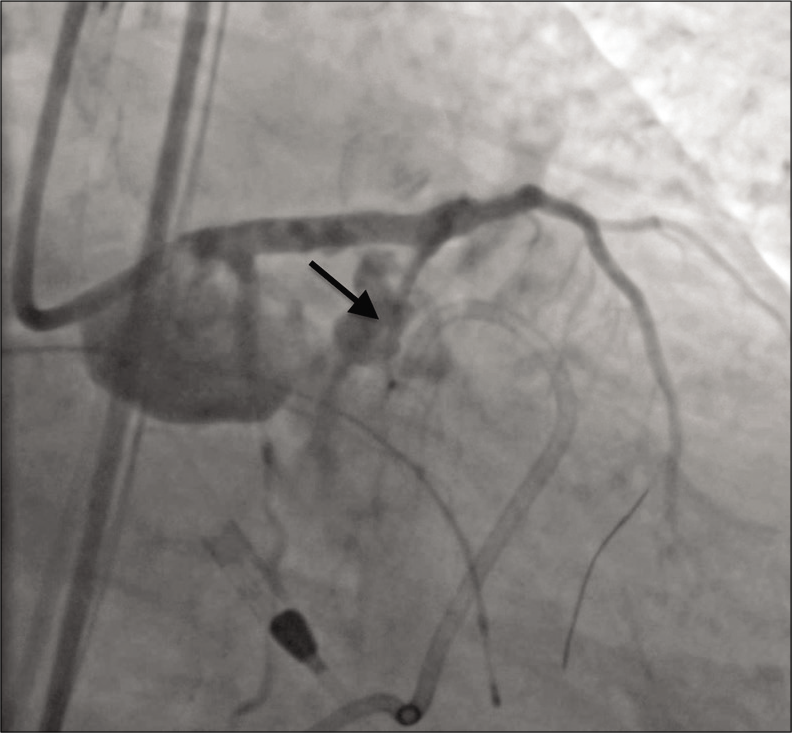

At this juncture, the patient suffered a cardiac arrest and interventional radiology was emergently consulted for assistance. Due to continued contrast extravasation and the patient’s unstable condition, it was decided to proceed with placement of a Viabahn stent graft. Balloon tamponade of the lesion was again performed, and additional access was obtained through an 8-French sheath in the left femoral artery. Utilizing a Thruway 0.0183 guidewire (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA), the interventional radiologist deployed a 6.0 mm × 50 mm Viabahn stent graft in the LAD and dilation was performed with a 5.0 mm balloon. Placement of the Viabahn stent graft resulted in excellent perfusion to the distal LAD but sacrificed a proximal diagonal branch of the LAD. Angiography after balloon dilation demonstrated no contrast extravasation [Figure 3].

- A 79-year-old male with 3 weeks of progressive dyspnea on exertion who was subsequently diagnosed with coronary artery disease involving the circumflex, right coronary, and left anterior descending arteries. Angiography showing resolution of contrast extravasation and excellent perfusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery after Viabahn stent graft placement (span of stent graft denoted by arrows).

The patient had return of spontaneous circulation and was successfully transferred to the intensive care unit on vasopressors. The patient received 17 units of packed red blood cells, eight units of fresh frozen plasma, two units of platelets, and 10 units of cryoprecipitate in the periprocedural period. Pericardial drain output totaled 2250 ml in the first 12 h post-procedure but resolved completely by post-procedure day 3. Troponin levels were not tracked in the post-procedural period. An echocardiogram performed 24 h post-procedure showed an ejection fraction of 27% with no pericardial effusion, and the patient was neurologically intact when he was extubated on post-procedure day 5. Eight days post-procedure, the patient was found to have a pneumonia. Despite treatment with vasopressors and antibiotics, the patient continued to experience severe septic/cardiogenic shock. On post-procedure day 11, the family elected to pursue comfort measures and the patient died the same day.

DISCUSSION

CAP is a relatively rare complication of PCI, with one systematic review and meta-analysis reporting CAP in just 0.43% of PCI cases.[1] When CAP does occur, it often results in serious sequelae. Cardiac tamponade and myocardial infarction occur in 20.8% and 19.3% of patients, respectively, and the overall mortality rate after CAP is 8.6%. In patients with Grade III CAP, rates of cardiac tamponade and myocardial infarction climb to 45.7% and 36.3%, respectively, and the mortality rate rises to 21.2%.[1] Patients developing tamponade physiology may have mortality rates as high as 25%.[4]

Treatment strategies for CAP largely depend on the grade of the lesion, which is typically described using the criteria set forth by Ellis et al.[5] For CAP Grades I and II, watchful waiting is often a reasonable approach. One study examining 37 patients with CAP Grades I and II utilized routine surveillance in 30 patients (81.0%) with no reported deaths. The remaining seven patients underwent stent graft placement or prolonged balloon inflation.[2] Grade III CAP is less likely to resolve spontaneously, and patients are more likely to need aggressive interventions including pericardiocentesis and emergent operations.[2]

In this case, CAP was secondary to stent placement and dilation in the proximal LAD. Shimony et al. found stent placement to be the cause of CAP in 21% of PCI cases, while wire perforation was the culprit in 53% of cases.[1] Several important risk factors for CAP were present in this patient including older age, hypercholesterolemia, LAD intervention, and use of a rotational atherectomy device.[6] Although prolonged balloon inflation and placement of a conventional coronary stent graft were performed in this patient, they proved to be futile. It was suspected that the stent graft failed to seal the perforation due to over dilation (3.0 mm PK Papyrus stent graft dilated to 5.0 mm) and disruption of the stent graft covering. The use of Viabahn stent grafts for severe CAP has not routinely been reported in the literature, but one case report describes the use of a 5.0 mm × 50 mm stent graft to treat a right CAP.[3] Viabahn stent grafts come in a variety of lengths and are composed of a robust polytetrafluoroethylene lining on an external nitinol support frame. In this case, a 6.0 mm stent graft was chosen since the 3.0 mm coronary-specific stent graft had already been inserted and overdilated to 5.0 mm without resolution of contrast extravasation. A 50 mm length was selected due to the catastrophic nature of the CAP and unknown length of the defect. The use of large stent grafts comes at the expense of potentially occluding branch vessels, which occurred in this patient with the blockage of a proximal diagonal branch of the LAD. Stent grafts used to treat CAP are also associated with high rates of stent thrombosis.[7,8] These risks may be acceptable in patients who are hemodynamically unstable or experiencing cardiac arrest, as in this case. In this patient, placement of a Viabahn stent graft successfully sealed the endoleak and resulted in immediate hemodynamic stabilization, although the patient ultimately died of septic/ cardiogenic shock on post-procedure day 11.

CONCLUSION

Severe cases of iatrogenic CAP may be refractory to stent graft placement and balloon tamponade. In cases of persistent contrast extravasation and endoleak, the use of peripheral arterial stent grafts may be of immediate clinical benefit.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Coronary artery perforation during percutaneous coronary intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27:843-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incidence, risk factors, management and outcomes of coronary artery perforation during percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1674-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viabahn stent graft in the management of a grade 3 coronary perforation. CVIR Endovasc. 2019;2:6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coronary artery perforation during percutaneous intervention: Incidence and outcome. Heart. 2002;88:495-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Increased coronary perforation in the new device era. Incidence, classification, management, and outcome. Circulation. 1994;90:2725-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incidence, determinants, and outcomes of coronary perforation during percutaneous coronary intervention in the United Kingdom between 2006 and 2013: An analysis of 527 121 cases from the British cardiovascular intervention society database. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:e003449.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and outcomes of coronary artery perforation during percutaneous coronary intervention. Eurointervention. 2017;13:e595-601.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical outcomes following covered stent for the treatment of coronary artery perforation. J Interv Cardiol. 2016;29:569-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]